Ralph Coburn: Radical Inventions

October 8 - November 5, 2024

David Hall Gallery

Working across canvases, drawings, and collages between France and the United States, Ralph Coburn redefined the contours of abstract art through a substantial body of work spanning from the late 1940s to the late 1980s. In close dialogue with Ellsworth Kelly during their formative years in France, Coburn’s innovative approach deconstructed the traditional conventions of painting, dismantling its spatial logic and reimagining its interaction with the viewer. He was among the first postwar artists to question the very foundations of the medium and propose a serious rethinking of the painted canvas format. Yet, his “radical” inventions —from the Latin etymology radix (meaning “root”)— deserve renewed attention today as the artist kept his early work hidden from the world for nearly fifty years. It is now time for a critical evaluation and renewed attention of Coburn’s ideas and his art.

After studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s School of Architecture and engaging with Boston’s burgeoning art scene, Ralph Coburn accepted an invitation from his friend Ellsworth Kelly to join him in France in early June 1949. Immersed in the vibrant atmosphere of postwar liberated Paris, Coburn found himself at a moment of extraordinary creative possibility and heuristic encounters where American and European avant-garde ideas intersected. Over four extended stays in France between 1949 and 1956, each lasting from six months to a year and a half, and interspersed with periods in Boston and New York, Coburn synthesized the transatlantic pictorial debates, developing a distinctive approach to abstraction. The seminal works featured in this exhibition, created between 1949 and 1962, epitomize this intense phase of experimentation and embody the sense of freedom that defined these early years.

During his first trip to France, Ralph Coburn delved deeper into abstraction and explored different styles and techniques. While visiting Brittany and the Côte d’Azur with Ellsworth Kelly, he introduced his compatriot to generative methods from New York and Boston’s Surrealist and Expressionist circles, such as doodling and automatic drawing. Coburn also refined his practice of distilling landscapes and objects—an extractive method he had employed since his architectural studies throughout the 1940s and further developed in France through his exchanges with Kelly. The latter had been creating similar stylized representations since the Spring of 1949, based on a compositional strategy that involved transferring forms from the visual world and translating them into paintings, drawings, or collages. As Debra Bricker Balken recently noted, the two “worked in tandem,” sometimes creating series based on shared motifs like the Seine River or the Swiss Pavilion of the Cité Universitaire.

At the same time, their approaches diverged significantly. Kelly’s method, termed “already made,” focused on the literal reproduction of an abstract motif observed in its visual environment to avoid traditional picture-building. Coburn, by contrast, embraced a process of “distillation,” where he freely abstracted and reinterpreted elements from the visual world. This inventive approach was likely shaped by his collaboration with architect Walter Netsch during his studies at MIT, a school that emphasized original concepts over replications. But a defining factor in Coburn’s practice was his lack of stereopsis, a condition that impaired his depth perception and led him to perceive the world as a flattened geometric plane. This condition prevented Coburn from being drafted for combat in 1944. Throughout his evolution from architecture student to draftsman for the Air Force during World War II and ultimately to abstract artist, Coburn’s “distillation” process remained central. It relied on two-dimensional plans, purifying and compressing objects and landscapes into disjunctive arrangements of surface and depth, plan and perspective, figure and ground.

Alongside young painters from the French art scene, such as Ellsworth Kelly, Georges Koskas, François Morellet, and Alain Naudé, Ralph Coburn explored geometric form through strategies of reduction and anti-composition to depersonalize painting and mitigate the artist’s subjectivity. Coburn’s interest in what he described as “making works of art that eventually take on an identity created by someone other than myself” deepened after two visits to Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber’s studio near Paris in 1950. Encountering the collaborative collages of the artist couple created “According to the Laws of Chance” in the 1910s, prompted Coburn to experiment with a new generative process involving chance through the technique of cutouts. Alongside Kelly, he was one of the first artists to employ randomness and indeterminacy as a compositional strategy, even before John Cage—whom he met in Paris with Merce Cunningham—began to work with chance in 1951.

Yet, it took no time for Coburn to realize that random methods were still shaped by artistic decisions regarding the pattern, size, color, or format. As a counterpoint, he created compositions “Arranged by Choice.” While the artist determined the formal elements, their placement was arranged randomly on a grid through the action of the viewers, who were invited to order the permutable units “by choice”. In essence, by enabling the work to evolve through external input rather than solely the artist’s decisions, Coburn significantly depersonalized the art-making process. This radical gesture redefined the roles of both artist and viewer, transforming the latter into a co-author and decision-maker. Ultimately, Coburn’s interactive method metamorphosed the work into a dynamic object, allowing the painting or collage to take on multiple, indefinite configurations.

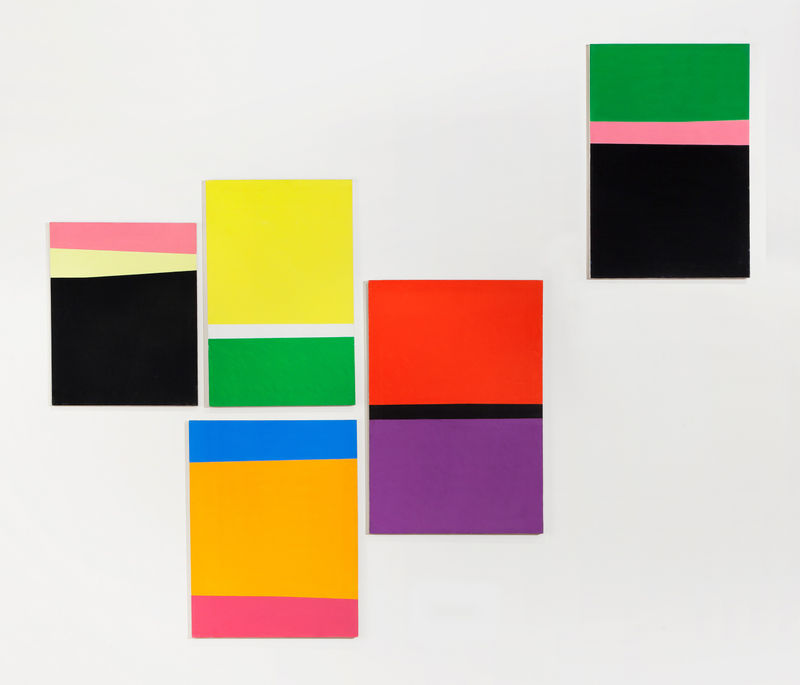

Other participatory and mobile explorations emerged within the French abstract art scene of the early 1950s, including William Klein’s multi-panel screens, Omar Carreño’s removable polyptychs, and the coplanar works of the Madí group, yet Coburn’s unit-panel grid system remained singular. Unlike his contemporaries, his movable multi-panels were not interconnected by metal rods or hinges, which only allowed limited mobility. Instead, each panel was intended to be entirely autonomous and movable on the wall, enabling configurations that were independent of the painting’s overall structure. This quest for the emancipation of pictorial elements culminated in Coburn’s emblematic series from the late 1950s and 1960s, known as “Random Sequence.” Here, he abandons the commonly orthogonal arrangement of canvases and grants the viewers even greater freedom to position the panels randomly on the wall at any interval, height, or orientation.

In the 1950s, the disruption of conventional tableau stability was gaining traction among Latin American circles based in Paris, particularly among Venezuelan painters from Los Disidentes and Argentine and Uruguayan artists from Madí. Gravitating within this milieu, Coburn was invited to exhibit in the Primera Muestra Internacional de Arte Abstracto at Galería Cuatro Muros in Caracas, Venezuela, in August and September 1952, showcasing alongside the most promising figures from these movements, including Carmelo Arden Quin, Alejandro Otero, and Jesús-Rafael Soto, as well as his friends Ellsworth Kelly, Georges Koskas, and Jack Youngerman. In the summers of 1950 and 1951, he showed several paintings at the prestigious Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, an annual exhibition in Paris dedicated exclusively to non-objective art. Additionally, his “distillation” View of Marseille was reproduced in a special issue on American painting in the non-objective journal Art d’Aujourd’hui in June 1951.

Although he actively participated in the French pictorial debates, Coburn, not being permanently based in Paris, found limited opportunities to exhibit his work in the capital. Gaining some recognition on the other side of the Atlantic, he accepted a position as a designer at MIT in 1957, where he remained until 1988. He

settled in the Boston area, quietly continuing his personal studio practice and producing an impressive body of work dedicated solely to painting and its compositional possibilities. His innovative methods and emphasis on viewer interaction established a pioneering pictorial paradigm that warrants reexamination and recognition today.

– Roxane Ilias

Roxane Ilias is a doctoral candidate at Université Paris-Sorbonne, where she studies the transformation of the tableau and the birth of painting objecthood after the Second World War. She has previously worked at Dia Art Foundation, New York, and Centre Pompidou, Paris, and her writings have been published by the Centre Pompidou, Cahiers du Musée d’Art Moderne, Cahiers de l’Ecole du Louvre, and more.